It’s a time of life when many may feel invincible, but adolescents are at risk of invasive meningococcal disease, a bacterial infection that can be life-threatening. Better disease awareness and knowledge about preventative options could help protect young people from the potentially devastating consequences.

At the end of a fun-filled, exhausting few weeks as a counsellor at a summer camp, 16-year-old Kate was not surprised to feel under the weather.

A couple of days after camp ended, she felt achy and feverish, which she’d put down to a regular bug. Less than 24 hours later, the teenager was air-lifted to the nearest major intensive care unit, fighting for her life.

The doctor said I was the sickest anyone could ever be, with the most life support anyone could ever be on,” says Kate.

“I was just about hanging on to life.”

Kate’s story is typical of an uncommon but dangerous condition known as invasive meningococcal disease or IMD. It is a severe bacterial infection that can lead to the swelling of fluid around the brain and spinal cord, known as meningitis, sepsis – a blood infection – or both. It tends to come on suddenly, becoming life-threatening within hours.

Doctors expect the worst when they see a case of IMD. Kate’s family were told to say goodbye as she was being transferred onto the air ambulance. That’s because in up to one in six cases, IMD proves fatal, and around 90% of deaths from IMD occur within 24 hours of diagnosis.

Kate was one of the lucky ones. She survived – but not without complications and a long road to recovery.

Ryan, 16, was not as fortunate.

His IMD symptoms started off mildly, much like Kate’s did. After waking up feeling very tired, he asked his mother, Michelle, to go out and buy him an energy drink. In the short time Michelle was away, Ryan suddenly deteriorated, and his 13-year-old sister called an ambulance. When Michelle returned, an unconscious Ryan was being rushed to hospital. By lunchtime, despite medical efforts to save him, her once strong, healthy son had died.

“His initial symptoms were the worst nightmare in that there weren’t any,” says Michelle.

“I’m often asking about the start, the during and the end, but there was no during. It just started and that was it. There just wasn’t anything we could do.”

And it doesn’t stop there. IMD often proves devastating even to those who make it through. Around one in five survivors are left with a lifelong condition. The sepsis that is often part of IMD, can lead to limb amputations and scarring. Other long-term complications include hearing loss, seizures, and difficulties with speech, vision and memory.

It often deeply affects its victim’s family and friends, too. Michelle says that Ryan’s death put a severe strain on her marriage, which eventually broke up.

“When there’s four of you, it’s like losing a leg of a table,” she says. “It just constantly wobbles and is never the same again.”

Meanwhile Kate’s parents came under financial and emotional strain taking time off work to care for her.

What causes IMD and why are young people at risk?

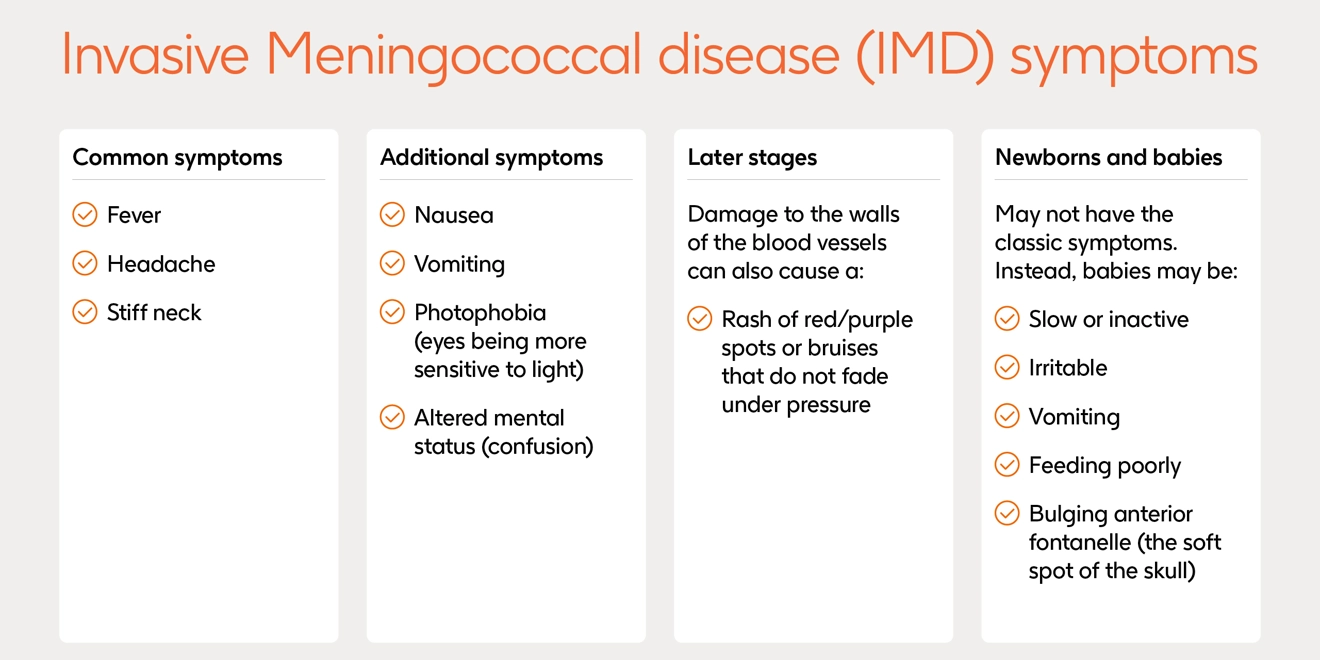

IMD is caused by meningococcus, a bacteria which can live without symptoms in the back of the throat and nose of around one in 10 people. On rare occasions, the bacteria can enter the bloodstream, leading to a potentially devastating infection. Common symptoms of IMD include a headache, fever and stiff neck, but these do not occur in all cases. IMD needs to be treated quickly with antibiotics, but prompt medical intervention does not always avert death.

Meningococcal bacteria are spread by respiratory droplets, which can be transmitted by close contact. IMD can affect people of any age, and while babies and young children are the most at risk because of their immature immune systems, teenagers and young adults are also regularly exposed to the disease.

This is due to behaviours that increase the spread of the bacteria, such as sleeping in dormitories, sharing utensils and mugs, and attending crowded events. Around one in four young people may also carry the disease asymptomatically. According to UK Government research, for example, there were 105 confirmed cases of IMD in England in 2023/24 in 10-to-24-year-olds, which made up around 30% of all cases.

There are 12 strains, or serogroups, of the meningococcal bacteria, five of which - known as groups A, B, C, W and Y – cause most cases of IMD globally.

How do we increase awareness of the risk of IMD?

Raising awareness among teenagers and young adults might include health systems working with high schools, colleges and universities to share knowledge about the risk of IMD. It could also include wider public health campaigns targeted at those groups – and the parents of younger teens.

“It’s necessary to stress the wider possibility of being protected, not only in children, where the system works very well, but in adolescents and in adults,” says Jan Smetana, Scientific Secretary of the Czech Vaccination Society.

Experts also agree that the governments can do more to support teenagers to access information about the signs and symptoms of IMD, the importance of seeking medical attention and how to reduce the risk of developing it. However, another barrier facing young people is that they don’t typically come into much contact with the healthcare system.

While babies and young children frequently visit doctors and other healthcare professionals for routine check-ups, teens can go years without seeing a doctor.

“Adolescents often feel invincible, and they’re in great health generally,” says Anar Andani, a Global Medical Affairs director at GSK. “They’re not going to proactively seek advice about IMD if they are unaware of it in the first instance.”

Advocates are another powerful way of communicating the risk of IMD, and to spread knowledge of preventative options. Ryan’s mother Michelle and Kate now dedicate much of their time to raising awareness of IMD among adolescents and their parents.

“I would love every parent of every young adult to have knowledge about IMD and to talk to those young adults about how they can help protect themselves from this deadly disease,” Michelle says.

“They've got their whole lives ahead of them.”

So what can young people do to reduce their risk?

There are several preventative measures young people can take to reduce their risk of contracting IMD.

On a personal level, observing good hygiene practices – such as routine and thorough hand washing, covering mouths and noses when coughing or sneezing, and limiting the sharing of utensils and drinks – could make a difference.

Immunisation could also reduce risk. Now, infants, who are at the highest risk of IMD, are typically vaccinated as part of national programmes, yet most countries do not routinely offer the same to young people, another key at-risk group. This makes the steps teenagers, young adults and parents take to educate themselves even more important.

“It is definitely worth people’s time to make an appointment to talk to a healthcare professional about meningitis and options to help prevent it,” Andani says.

“Tools and advice are available and parents, teens and young adults should feel encouraged to take the initiative to put the topic on the table with their health care provider, given that the consequences of IMD can be devastating for patients and their families.”

Peer-to-peer communication, through young people sharing information from validated sources, such as public health bodies and registered advocacy groups, could also make an impact.

“I want to keep talking about [IMD] until everyone is aware of the dangers of this disease and how prevent it,” Kate, herself a peer-to-peer advocate, concludes.

“I want young people to be highly aware of what’s happening in their own bodies and environments so that they can properly take care of themselves.”