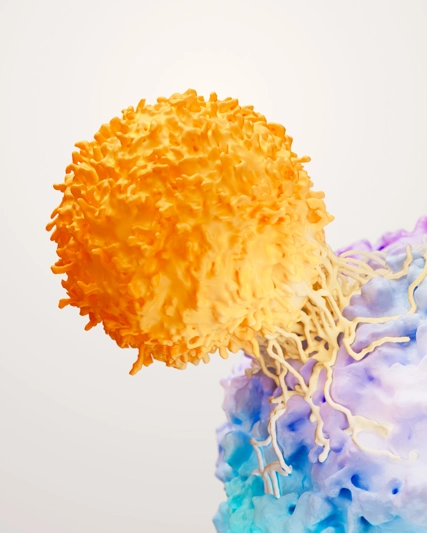

Many blood cancers require lifelong treatment, but some medicines can cause debilitating side effects – and require frequent hospital visits to administer. Now, scientists are working hard to find new solutions and give patients the quality of life they deserve.

Ask most people to describe cancer and they will likely say it is a tumour, a lump or a growth. For most malignancies, this is true, but there is one group of cancers that doesn’t fit the norm.

Blood cancers account for around 10% of all cancer diagnoses, and a quarter of all cancer diagnoses in children. They start in the blood, bone marrow or lymphatic system, and affect how blood cells grow and function. As a result, the normal production of blood cells is disrupted, weakening the immune system, and causing infections and bleeding issues.

Many symptoms of blood cancer – such as bone pain, tiredness and night sweats – are easily attributed to less serious conditions, which can make them more difficult to diagnose than solid tumours.

“If you have the chance to diagnose a solid tumour soon enough, your primary goal is to remove the cancer through surgery,” says Dr Ali Cimen, SVP, Global Medical Affairs, Oncology at GSK.

“On the other hand, in blood cancer, nearly all the time your treatment option is systemic therapy, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy. There is no surgery except for a few cases.”

There are many forms of blood cancer, depending on which part of the blood is affected. The best known – and most common – types of blood cancer are lymphoma and leukaemia.

Lymphoma, which makes up nearly half of all blood cancer diagnoses, occurs when lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, multiply uncontrollably. Leukaemia, the next most common blood cancer, affects the production of white blood cells in the bone marrow. Together, they account for around 80% of all blood cancer diagnoses.

Less well known are the myelomas, which affect the production of plasma cells, a type of white blood cell, in the bone marrow. Around 19% of blood cancer diagnoses, or around 2% of all cancers, are myelomas.

And then there is myelofibrosis, part of a rarer category of blood cancers known as myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Living with blood cancer

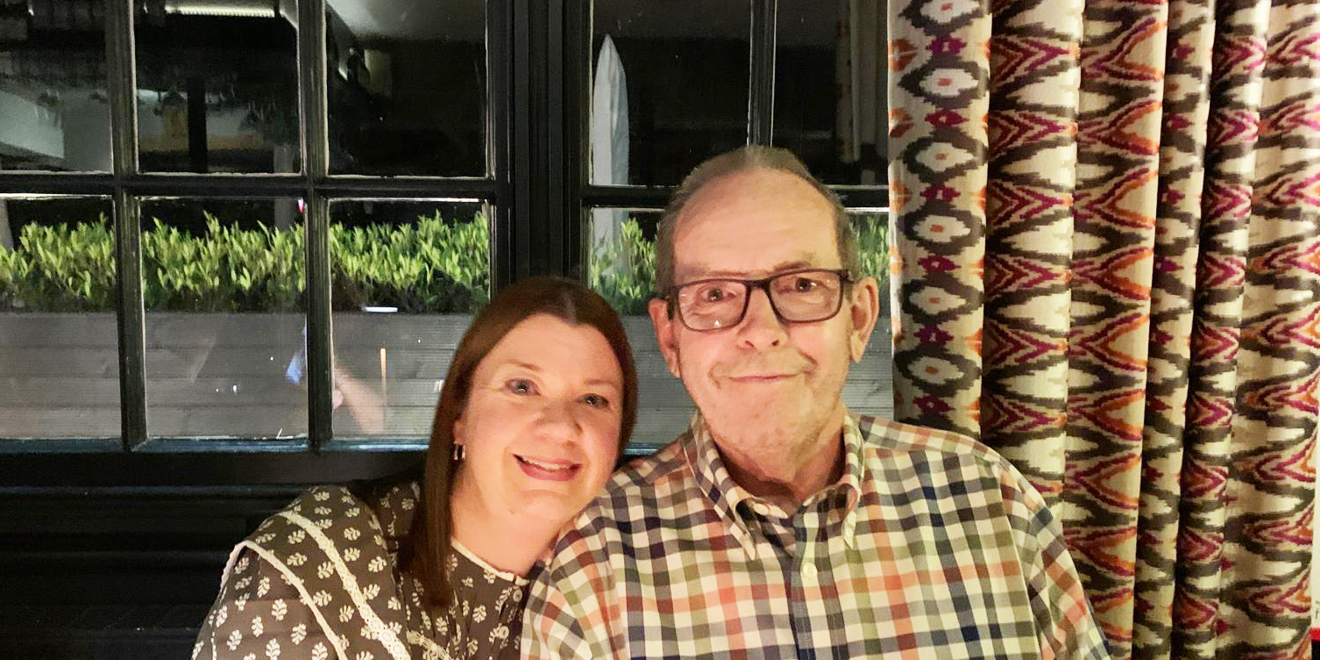

For Dave, 72, from High Wycombe, UK, the journey to a blood cancer diagnosis began when tests for an unrelated heart condition produced abnormal results.

Months later, after extensive testing for other more common causes, his doctors discovered that he had myelofibrosis, a very rare form of blood cancer that only affects around 1.5 in every 100,000 people. Myelofibrosis causes scar tissue to build up in the bone marrow, causing an overproduction of unhealthy blood cells. Unlike some other forms of blood cancer, it tends to progress slowly.

“As soon as I mentioned to anyone that I had blood cancer, they naturally assumed that I was going to die quite quickly and had leukaemia, which was the only blood cancer that people really thought about,” says Dave.

Lou, 47, from Newbury, UK has multiple myeloma. She found it difficult to describe her diagnosis to her friends and family.

“I had to explain to them what multiple myeloma was, because nobody's heard of it,” she said.

“And when you explain that it's incurable, people don't actually understand that.”

Some forms of blood cancer are curable. But for many patients, a blood cancer diagnosis is the beginning of a lifelong journey of treatment to manage the disease as a chronic condition.

“It's quite hard to explain to people that you're about to start this journey, it's going to change your life as all cancer diagnoses do, but it's not really going to end,” she says.

“It goes on…[doctors] keep you on permanent treatment, to keep the myeloma at bay for as long as possible. And so it's a continuous journey.

“I sometimes prefer to explain it as in: the myeloma is asleep at the minute. It's not active, it's asleep, but it will wake up.”

Getting treated

For Lou, a successful bone marrow transplant subdued her multiple myeloma.

Stem cells, found in bone marrow, are the body’s blood cell factories, and blood cancers occur when something goes wrong with them. Replacing unhealthy stem cells with healthy ones can slow down the progression of some blood cancers – and in some cases potentially cure them.

However, the procedure is complex and risky – and involves suppressing the immune system. That means it is not suitable for everyone, particularly those who are older or have other health issues. They also often depend on stem cells from a matched donor, which are not always available.

After her stem cell transplant, Lou was put on three different drugs to keep her cancer at bay, a treatment that required frequent hospital visits for infusions. After 18 months, she switched to just one of those drugs, which can be taken in pill form at home.

“I'm feeling a little bit more like my old self for the first time since my diagnosis,” she says.

However, she still suffers from bouts of severe fatigue: “I often feel quite hopeless and frustrated because I used to be very lively and very energetic.

“And to suddenly be a person who can barely think straight, forgets what they're talking about and can't get off the sofa, it is really hard to deal with.”

Dave also expects to remain on treatment for the rest of his life. Like many patients, a stem cell transplant was not an option for him due to his other health issues. Instead, he was given a drug to reduce the swelling in his spleen, a common manifestation of myelofibrosis. Unfortunately, that medication reduced his levels of haemoglobin – a complex protein found in red blood cells that contains an iron molecule – causing anaemia.

As a result, he suffered from severe fatigue and had to travel to a hospital for routine blood transfusions. He and his wife Frances, who is also his primary carer, stopped taking holidays abroad, fearful of a medical emergency. If they travelled within the UK, they did so immediately following a transfusion, when he felt most well.

Of his worst days, he says: “We got to a situation where, if I'm honest, I could hardly walk up and down the street… Sometimes I couldn't really do anything.”

Medical advances

Thankfully many blood cancer patients are now living longer due to the advancement of treatment options in cancer care.

Yet, more advances are still needed. Not just to improve the quality of life for patients, but because, despite all this progress, 60% of multiple myeloma cases in the US survive for just five years – and almost all experience relapses at some point.

“That's because we don't have a cure, and these patients will continue to have relapses over time, and the majority of these patients, they remain on continuous treatment,” says C. Ola Landgren, MD, PhD Director of the Sylvester Myeloma Institute at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami.

“So, the burden on society, and on individual people's lives, is substantial.”

And despite extensions in survival for most people with multiple myeloma, around 10% of patients don’t respond well to standard treatment regimens.

“The lifespan of these patients, where the disease keeps on coming back like this, is very, very different from the majority of patients,” says Dr Landgren.

“The disease is handled as a single disease, but it’s not a single disease. The only way we can solve this is by developing more sophisticated tools for profiling of the disease, and to use this to change the treatment for these patients.”

Now, scientists are doing exactly that: pursuing new tools and treatments to address the issues faced by chronic blood cancer patients.

At GSK, this includes advancing understanding of the underlying drivers of cancer using translational science, which combines basic research with clinical trials to improve real-world patient outcomes. This research can result in better clinical trial designs, more accurate predictions of how patients will respond to treatment, and therapies that are more durable and have fewer side effects.

Researchers are also working to discover new classes of drug that can lengthen disease-free survival, developing medicines that are more tolerable, targeting treatments to the patients who will most benefit from them, and coming up with options that can be administered at home or in a community setting.

"Our common goal is to eliminate cancer as a cause of death [but] when we are left with a disease which we know we cannot cure, our main treatment goal is to have the disease-free interval as long as possible," says Dr Cimen.

“Everything that compromises patients’ quality of life or adverse events, especially the ones which may require additional interventions or hospitalisations, are all burdens not only to the patient, but also to the healthcare systems and the carers and the families.”

Dave’s life changed when, after 18 months of blood transfusions, he was switched to a different treatment that controlled the size of his spleen without causing his haemoglobin levels to plummet.

He and Frances finally took a holiday abroad and he is now able to enjoy long walks again.

Meanwhile, Lou remains hopeful that innovative discoveries will help her manage her blood cancer for years to come.

“It is becoming more and more important to remember that those patients also have a life to live,” Dr Cimen concludes.

“We don’t only want those patients to have more years in their lives, but we also want them to have more life in their years.”